Importance The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, due to the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has caused a worldwide sudden and substantial increase in hospitalizations for pneumonia with multiorgan disease. This review discusses current evidence regarding the pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and management of COVID-19.

Observations SARS-CoV-2 is spread primarily via respiratory droplets during close face-to-face contact. Infection can be spread by asymptomatic, presymptomatic, and symptomatic carriers. The average time from exposure to symptom onset is 5 days, and 97.5% of people who develop symptoms do so within 11.5 days. The most common symptoms are fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath. Radiographic and laboratory abnormalities, such as lymphopenia and elevated lactate dehydrogenase, are common, but nonspecific. Diagnosis is made by detection of SARS-CoV-2 via reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing, although false-negative test results may occur in up to 20% to 67% of patients; however, this is dependent on the quality and timing of testing. Manifestations of COVID-19 include asymptomatic carriers and fulminant disease characterized by sepsis and acute respiratory failure. Approximately 5% of patients with COVID-19, and 20% of those hospitalized, experience severe symptoms necessitating intensive care. More than 75% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 require supplemental oxygen. Treatment for individuals with COVID-19 includes best practices for supportive management of acute hypoxic respiratory failure. Emerging data indicate that dexamethasone therapy reduces 28-day mortality in patients requiring supplemental oxygen compared with usual care (21.6% vs 24.6%; age-adjusted rate ratio, 0.83 [95% CI, 0.74-0.92]) and that remdesivir improves time to recovery (hospital discharge or no supplemental oxygen requirement) from 15 to 11 days. In a randomized trial of 103 patients with COVID-19, convalescent plasma did not shorten time to recovery. Ongoing trials are testing antiviral therapies, immune modulators, and anticoagulants. The case-fatality rate for COVID-19 varies markedly by age, ranging from 0.3 deaths per 1000 cases among patients aged 5 to 17 years to 304.9 deaths per 1000 cases among patients aged 85 years or older in the US. Among patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit, the case fatality is up to 40%. At least 120 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are under development. Until an effective vaccine is available, the primary methods to reduce spread are face masks, social distancing, and contact tracing. Monoclonal antibodies and hyperimmune globulin may provide additional preventive strategies.

Conclusions and Relevance As of July 1, 2020, more than 10 million people worldwide had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Many aspects of transmission, infection, and treatment remain unclear. Advances in prevention and effective management of COVID-19 will require basic and clinical investigation and public health and clinical interventions.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused a sudden significant increase in hospitalizations for pneumonia with multiorgan disease. COVID-19 is caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 infection may be asymptomatic or it may cause a wide spectrum of symptoms, such as mild symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection and life-threatening sepsis. COVID-19 first emerged in December 2019, when a cluster of patients with pneumonia of unknown cause was recognized in Wuhan, China. As of July 1, 2020, SARS-CoV-2 has affected more than 200 countries, resulting in more than 10 million identified cases with 508 000 confirmed deaths (Figure 1). This review summarizes current evidence regarding pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and management of COVID-19.

We searched PubMed, LitCovid, and MedRxiv using the search terms coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, 2019-nCoV, SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and COVID-19 for studies published from January 1, 2002, to June 15, 2020, and manually searched the references of select articles for additional relevant articles. Ongoing or completed clinical trials were identified using the disease search term coronavirus infection on ClinicalTrials.gov, the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. We selected articles relevant to a general medicine readership, prioritizing randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews, and clinical practice guidelines.

Coronaviruses are large, enveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses found in humans and other mammals, such as dogs, cats, chicken, cattle, pigs, and birds. Coronaviruses cause respiratory, gastrointestinal, and neurological disease. The most common coronaviruses in clinical practice are 229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1, which typically cause common cold symptoms in immunocompetent individuals. SARS-CoV-2 is the third coronavirus that has caused severe disease in humans to spread globally in the past 2 decades.1 The first coronavirus that caused severe disease was severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which was thought to originate in Foshan, China, and resulted in the 2002-2003 SARS-CoV pandemic.2 The second was the coronavirus-caused Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which originated from the Arabian peninsula in 2012.3

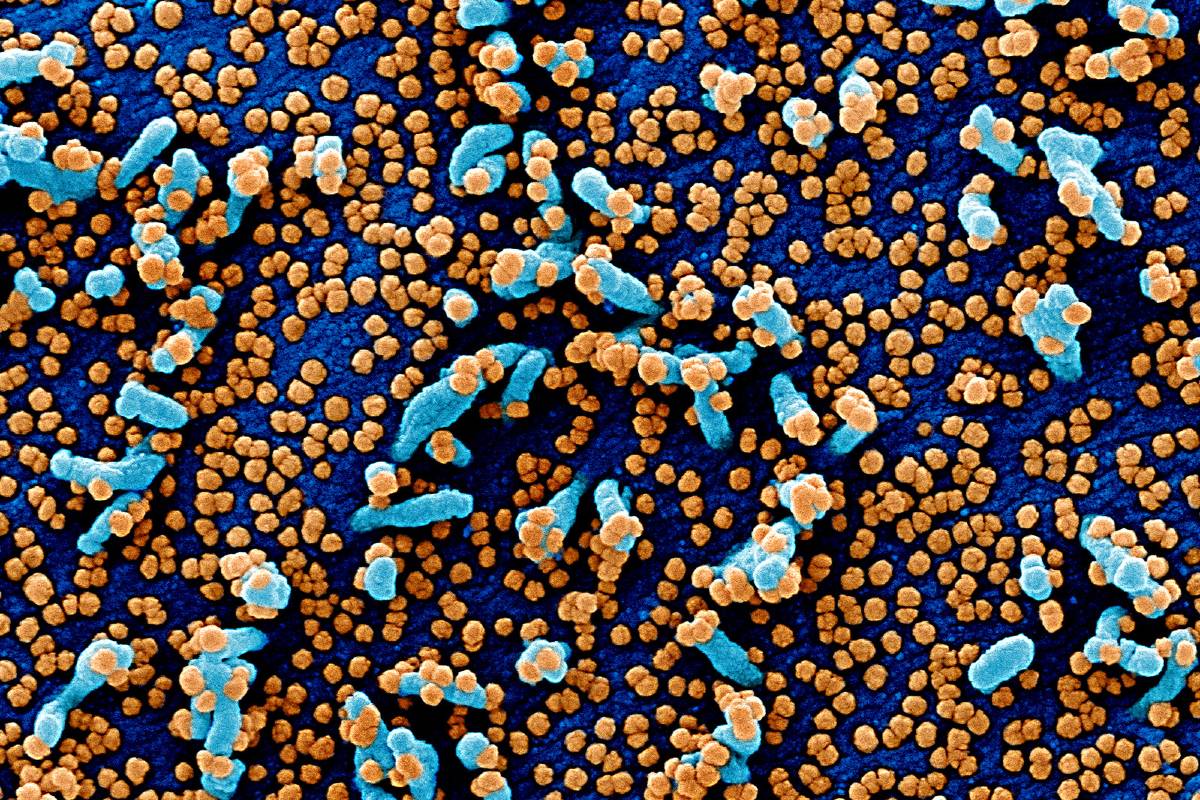

SARS-CoV-2 has a diameter of 60 nm to 140 nm and distinctive spikes, ranging from 9 nm to 12 nm, giving the virions the appearance of a solar corona (Figure 2).4 Through genetic recombination and variation, coronaviruses can adapt to and infect new hosts. Bats are thought to be a natural reservoir for SARS-CoV-2, but it has been suggested that humans became infected with SARS-CoV-2 via an intermediate host, such as the pangolin.5,6

The Host Defense Against SARS-CoV-2

Early in infection, SARS-CoV-2 targets cells, such as nasal and bronchial epithelial cells and pneumocytes, through the viral structural spike (S) protein that binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor7 (Figure 2). The type 2 transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2), present in the host cell, promotes viral uptake by cleaving ACE2 and activating the SARS-CoV-2 S protein, which mediates coronavirus entry into host cells.7 ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed in host target cells, particularly alveolar epithelial type II cells.8,9 Similar to other respiratory viral diseases, such as influenza, profound lymphopenia may occur in individuals with COVID-19 when SARS-CoV-2 infects and kills T lymphocyte cells. In addition, the viral inflammatory response, consisting of both the innate and the adaptive immune response (comprising humoral and cell-mediated immunity), impairs lymphopoiesis and increases lymphocyte apoptosis. Although upregulation of ACE2 receptors from ACE inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker medications has been hypothesized to increase susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, large observational cohorts have not found an association between these medications and risk of infection or hospital mortality due to COVID-19.10,11 For example, in a study 4480 patients with COVID-19 from Denmark, previous treatment with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers was not associated with mortality.11

In later stages of infection, when viral replication accelerates, epithelial-endothelial barrier integrity is compromised. In addition to epithelial cells, SARS-CoV-2 infects pulmonary capillary endothelial cells, accentuating the inflammatory response and triggering an influx of monocytes and neutrophils. Autopsy studies have shown diffuse thickening of the alveolar wall with mononuclear cells and macrophages infiltrating airspaces in addition to endothelialitis.12 Interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates and edema develop and appear as ground-glass opacities on computed tomographic imaging. Pulmonary edema filling the alveolar spaces with hyaline membrane formation follows, compatible with early-phase acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).12 Bradykinin-dependent lung angioedema may contribute to disease.13 Collectively, endothelial barrier disruption, dysfunctional alveolar-capillary oxygen transmission, and impaired oxygen diffusion capacity are characteristic features of COVID-19.

In severe COVID-19, fulminant activation of coagulation and consumption of clotting factors occur.14,15 A report from Wuhan, China, indicated that 71% of 183 individuals who died of COVID-19 met criteria for diffuse intravascular coagulation.14 Inflamed lung tissues and pulmonary endothelial cells may result in microthrombi formation and contribute to the high incidence of thrombotic complications, such as deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and thrombotic arterial complications (eg, limb ischemia, ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction) in critically ill patients.16 The development of viral sepsis, defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, may further contribute to multiorgan failure.

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Epidemiologic data suggest that droplets expelled during face-to-face exposure during talking, coughing, or sneezing is the most common mode of transmission (Box 1). Prolonged exposure to an infected person (being within 6 feet for at least 15 minutes) and briefer exposures to individuals who are symptomatic (eg, coughing) are associated with higher risk for transmission, while brief exposures to asymptomatic contacts are less likely to result in transmission.25 Contact surface spread (touching a surface with virus on it) is another possible mode of transmission. Transmission may also occur via aerosols (smaller droplets that remain suspended in air), but it is unclear if this is a significant source of infection in humans outside of a laboratory setting.26,27 The existence of aerosols in physiological states (eg, coughing) or the detection of nucleic acid in the air does not mean that small airborne particles are infectious.28 Maternal COVID-19 is currently believed to be associated with low risk for vertical transmission. In most reported series, the mothers’ infection with SARS-CoV-2 occurred in the third trimester of pregnancy, with no maternal deaths and a favorable clinical course in the neonates.29–31

Box 1.

Transmission, Symptoms, and Complications of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

-

Transmission17 of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) occurs primarily via respiratory droplets from face-to-face contact and, to a lesser degree, via contaminated surfaces. Aerosol spread may occur, but the role of aerosol spread in humans remains unclear. An estimated 48% to 62% of transmission may occur via presymptomatic carriers.

-

Common symptoms18 in hospitalized patients include fever (70%-90%), dry cough (60%-86%), shortness of breath (53%-80%), fatigue (38%), myalgias (15%-44%), nausea/vomiting or diarrhea (15%-39%), headache, weakness (25%), and rhinorrhea (7%). Anosmia or ageusia may be the sole presenting symptom in approximately 3% of individuals with COVID-19.

-

Common laboratory abnormalities19 among hospitalized patients include lymphopenia (83%), elevated inflammatory markers (eg, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, ferritin, tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1, IL-6), and abnormal coagulation parameters (eg, prolonged prothrombin time, thrombocytopenia, elevated D-dimer [46% of patients], low fibrinogen).

-

Common radiographic findings of individuals with COVID-19 include bilateral, lower-lobe predominate infiltrates on chest radiographic imaging and bilateral, peripheral, lower-lobe ground-glass opacities and/or consolidation on chest computed tomographic imaging.

-

Common complications18,20–24 among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 include pneumonia (75%); acute respiratory distress syndrome (15%); acute liver injury, characterized by elevations in aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and bilirubin (19%); cardiac injury, including troponin elevation (7%-17%), acute heart failure, dysrhythmias, and myocarditis; prothrombotic coagulopathy resulting in venous and arterial thromboembolic events (10%-25%); acute kidney injury (9%); neurologic manifestations, including impaired consciousness (8%) and acute cerebrovascular disease (3%); and shock (6%).

-

Rare complications among critically ill patients with COVID-19 include cytokine storm and macrophage activation syndrome (ie, secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis).

The clinical significance of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from inanimate surfaces is difficult to interpret without knowing the minimum dose of virus particles that can initiate infection. Viral load appears to persist at higher levels on impermeable surfaces, such as stainless steel and plastic, than permeable surfaces, such as cardboard.32 Virus has been identified on impermeable surfaces for up to 3 to 4 days after inoculation.32 Widespread viral contamination of hospital rooms has been documented.28 However, it is thought that the amount of virus detected on surfaces decays rapidly within 48 to 72 hours.32 Although the detection of virus on surfaces reinforces the potential for transmission via fomites (objects such as a doorknob, cutlery, or clothing that may be contaminated with SARS-CoV-2) and the need for adequate environmental hygiene, droplet spread via face-to-face contact remains the primary mode of transmission.

Viral load in the upper respiratory tract appears to peak around the time of symptom onset and viral shedding begins approximately 2 to 3 days prior to the onset of symptoms.33 Asymptomatic and presymptomatic carriers can transmit SARS-CoV-2.34,35 In Singapore, presymptomatic transmission has been described in clusters of patients with close contact (eg, through churchgoing or singing class) approximately 1 to 3 days before the source patient developed symptoms.34 Presymptomatic transmission is thought to be a major contributor to the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Modeling studies from China and Singapore estimated the percentage of infections transmitted from a presymptomatic individual as 48% to 62%.17 Pharyngeal shedding is high during the first week of infection at a time in which symptoms are still mild, which might explain the efficient transmission of SARS-CoV-2, because infected individuals can be infectious before they realize they are ill.36 Although studies have described rates of asymptomatic infection, ranging from 4% to 32%, it is unclear whether these reports represent truly asymptomatic infection by individuals who never develop symptoms, transmission by individuals with very mild symptoms, or transmission by individuals who are asymptomatic at the time of transmission but subsequently develop symptoms.37–39 A systematic review on this topic suggested that true asymptomatic infection is probably uncommon.38

Although viral nucleic acid can be detectable in throat swabs for up to 6 weeks after the onset of illness, several studies suggest that viral cultures are generally negative for SARS-CoV-2 8 days after symptom onset.33,36,40 This is supported by epidemiological studies that have shown that transmission did not occur to contacts whose exposure to the index case started more than 5 days after the onset of symptoms in the index case.41 This suggests that individuals can be released from isolation based on clinical improvement. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend isolating for at least 10 days after symptom onset and 3 days after improvement of symptoms.42 However, there remains uncertainty about whether serial testing is required for specific subgroups, such as immunosuppressed patients or critically ill patients for whom symptom resolution may be delayed or older adults residing in short- or long-term care facilities.

The mean (interquartile range) incubation period (the time from exposure to symptom onset) for COVID-19 is approximately 5 (2-7) days.43,44 Approximately 97.5% of individuals who develop symptoms will do so within 11.5 days of infection.43 The median (interquartile range) interval from symptom onset to hospital admission is 7 (3-9) days.45 The median age of hospitalized patients varies between 47 and 73 years, with most cohorts having a male preponderance of approximately 60%.44,46,47 Among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, 74% to 86% are aged at least 50 years.45,47

COVID-19 has various clinical manifestations (Box 1 and Box 2). In a study of 44 672 patients with COVID-19 in China, 81% of patients had mild manifestations, 14% had severe manifestations, and 5% had critical manifestations (defined by respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction).48 A study of 20 133 individuals hospitalized with COVID-19 in the UK reported that 17.1% were admitted to high-dependency or intensive care units (ICUs).47

Box 2.

Commonly Asked Questions About Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

-

How is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) most commonly transmitted?

-

SARS-CoV-2 is most commonly spread via respiratory droplets (eg, from coughing, sneezing, shouting) during face-to-face exposure or by surface contamination.

-

What are the most common symptoms of COVID-19?

-

The 3 most common symptoms are fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Additional symptoms include weakness, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, changes to taste and smell.

-

How is the diagnosis made?

-

Diagnosis of COVID-19 is typically made by polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal swab. However, given the possibility of false-negative test results, clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings may also be used to make a presumptive diagnosis for individuals for whom there is a high index of clinical suspicion of infection.

-

What are current evidence-based treatments for individuals with COVID-19?

-

Supportive care, including supplemental oxygen, is the main treatment for most patients. Recent trials indicate that dexamethasone decreases mortality (subgroup analysis suggests benefit is limited to patients who require supplemental oxygen and who have symptoms for >7 d) and remdesivir improves time to recovery (subgroup analysis suggests benefit is limited to patients not receiving mechanical ventilation).

-

What percentage of people are asymptomatic carriers, and how important are they in transmitting the disease?

-

Are masks effective at preventing spread?

-

Yes. Face masks reduce the spread of viral respiratory infection. N95 respirators and surgical masks both provide substantial protection (compared with no mask), and surgical masks provide greater protection than cloth masks. However, physical distancing is also associated with substantial reduction of viral transmission, with greater distances providing greater protection. Additional measures such as hand and environmental disinfection are also important.

Although only approximately 25% of infected patients have comorbidities, 60% to 90% of hospitalized infected patients have comorbidities.45–49 The most common comorbidities in hospitalized patients include hypertension (present in 48%-57% of patients), diabetes (17%-34%), cardiovascular disease (21%-28%), chronic pulmonary disease (4%-10%), chronic kidney disease (3%-13%), malignancy (6%-8%), and chronic liver disease (<5%).45,46,49

The most common symptoms in hospitalized patients are fever (up to 90% of patients), dry cough (60%-86%), shortness of breath (53%-80%), fatigue (38%), nausea/vomiting or diarrhea (15%-39%), and myalgia (15%-44%).18,44–47,49,50 Patients can also present with nonclassical symptoms, such as isolated gastrointestinal symptoms.18 Olfactory and/or gustatory dysfunctions have been reported in 64% to 80% of patients.51–53 Anosmia or ageusia may be the sole presenting symptom in approximately 3% of patients.53

Complications of COVID-19 include impaired function of the heart, brain, lung, liver, kidney, and coagulation system. COVID-19 can lead to myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, ventricular arrhythmias, and hemodynamic instability.20,54 Acute cerebrovascular disease and encephalitis are observed with severe illness (in up to 8% of patients).21,52 Venous and arterial thromboembolic events occur in 10% to 25% in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.19,22 In the ICU, venous and arterial thromboembolic events may occur in up to 31% to 59% of patients with COVID-19.16,22

Approximately 17% to 35% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are treated in an ICU, most commonly due to hypoxemic respiratory failure. Among patients in the ICU with COVID-19, 29% to 91% require invasive mechanical ventilation.47,49,55,56 In addition to respiratory failure, hospitalized patients may develop acute kidney injury (9%), liver dysfunction (19%), bleeding and coagulation dysfunction (10%-25%), and septic shock (6%).18,19,23,49,56

Approximately 2% to 5% of individuals with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 are younger than 18 years, with a median age of 11 years. Children with COVID-19 have milder symptoms that are predominantly limited to the upper respiratory tract, and rarely require hospitalization. It is unclear why children are less susceptible to COVID-19. Potential explanations include that children have less robust immune responses (ie, no cytokine storm), partial immunity from other viral exposures, and lower rates of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Although most pediatric cases are mild, a small percentage (<7%) of children admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 develop severe disease requiring mechanical ventilation.57 A rare multisystem inflammatory syndrome similar to Kawasaki disease has recently been described in children in Europe and North America with SARS-CoV-2 infection.58,59 This multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children is uncommon (2 in 100 000 persons aged <21 years).60

Diagnosis of COVID-19 is typically made using polymerase chain reaction testing via nasal swab (Box 2). However, because of false-negative test result rates of SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing of nasal swabs, clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings may also be used to make a presumptive diagnosis.

Diagnostic Testing: Polymerase Chain Reaction and Serology

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction–based SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection from respiratory samples (eg, nasopharynx) is the standard for diagnosis. However, the sensitivity of testing varies with timing of testing relative to exposure. One modeling study estimated sensitivity at 33% 4 days after exposure, 62% on the day of symptom onset, and 80% 3 days after symptom onset.61–63 Factors contributing to false-negative test results include the adequacy of the specimen collection technique, time from exposure, and specimen source. Lower respiratory samples, such as bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, are more sensitive than upper respiratory samples. Among 1070 specimens collected from 205 patients with COVID-19 in China, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimens had the highest positive rates of SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing results (93%), followed by sputum (72%), nasal swabs (63%), and pharyngeal swabs (32%).61 SARS-CoV-2 can also be detected in feces, but not in urine.61 Saliva may be an alternative specimen source that requires less personal protective equipment and fewer swabs, but requires further validation.64

Several serological tests can also aid in the diagnosis and measurement of responses to novel vaccines.62,65,66 However, the presence of antibodies may not confer immunity because not all antibodies produced in response to infection are neutralizing. Whether and how frequently second infections with SARS-CoV-2 occur remain unknown. Whether presence of antibody changes susceptibility to subsequent infection or how long antibody protection lasts are unknown. IgM antibodies are detectable within 5 days of infection, with higher IgM levels during weeks 2 to 3 of illness, while an IgG response is first seen approximately 14 days after symptom onset.62,65 Higher antibody titers occur with more severe disease.66 Available serological assays include point-of-care assays and high throughput enzyme immunoassays. However, test performance, accuracy, and validity are variable.67

A systematic review of 19 studies of 2874 patients who were mostly from China (mean age, 52 years), of whom 88% were hospitalized, reported the typical range of laboratory abnormalities seen in COVID-19, including elevated serum C-reactive protein (increased in >60% of patients), lactate dehydrogenase (increased in approximately 50%-60%), alanine aminotransferase (elevated in approximately 25%), and aspartate aminotransferase (approximately 33%).24 Approximately 75% of patients had low albumin.24 The most common hematological abnormality is lymphopenia (absolute lymphocyte count <1.0 × 109/L), which is present in up to 83% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19.44,50 In conjunction with coagulopathy, modest prolongation of prothrombin times (prolonged in >5% of patients), mild thrombocytopenia (present in approximately 30% of patients) and elevated D-dimer values (present in 43%-60% of patients) are common.14,15,19,44,68 However, most of these laboratory characteristics are nonspecific and are common in pneumonia. More severe laboratory abnormalities have been associated with more severe infection.44,50,69 D-dimer and, to a lesser extent, lymphopenia seem to have the largest prognostic associations.69

The characteristic chest computed tomographic imaging abnormalities for COVID-19 are diffuse, peripheral ground-glass opacities (Figure 3).70 Ground-glass opacities have ill-defined margins, air bronchograms, smooth or irregular interlobular or septal thickening, and thickening of the adjacent pleura.70 Early in the disease, chest computed tomographic imaging findings in approximately 15% of individuals and chest radiograph findings in approximately 40% of individuals can be normal.44 Rapid evolution of abnormalities can occur in the first 2 weeks after symptom onset, after which they subside gradually.70,71

Chest computed tomographic imaging findings are nonspecific and overlap with other infections, so the diagnostic value of chest computed tomographic imaging for COVID-19 is limited. Some patients admitted to the hospital with polymerase chain reaction testing–confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection have normal computed tomographic imaging findings, while abnormal chest computed tomographic imaging findings compatible with COVID-19 occur days before detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in other patients.70,71

Supportive Care and Respiratory Support

Currently, best practices for supportive management of acute hypoxic respiratory failure and ARDS should be followed.72–74 Evidence-based guideline initiatives have been established by many countries and professional societies,72–74 including guidelines that are updated regularly by the National Institutes of Health.74

More than 75% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 require supplemental oxygen therapy. For patients who are unresponsive to conventional oxygen therapy, heated high-flow nasal canula oxygen may be administered.72 For patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, lung-protective ventilation with low tidal volumes (4-8 mL/kg, predicted body weight) and plateau pressure less than 30 mg Hg is recommended.72 Additionally, prone positioning, a higher positive end-expiratory pressure strategy, and short-term neuromuscular blockade with cisatracurium or other muscle relaxants may facilitate oxygenation. Although some patients with COVID-19–related respiratory failure have high lung compliance,75 they are still likely to benefit from lung-protective ventilation.76 Cohorts of patients with ARDS have displayed similar heterogeneity in lung compliance, and even patients with greater compliance have shown benefit from lower tidal volume strategies.76

The threshold for intubation in COVID-19–related respiratory failure is controversial, because many patients have normal work of breathing but severe hypoxemia.77 “Earlier” intubation allows time for a more controlled intubation process, which is important given the logistical challenges of moving patients to an airborne isolation room and donning personal protective equipment prior to intubation. However, hypoxemia in the absence of respiratory distress is well tolerated, and patients may do well without mechanical ventilation. Earlier intubation thresholds may result in treating some patients with mechanical ventilation unnecessarily and exposing them to additional complications. Currently, insufficient evidence exists to make recommendations regarding earlier vs later intubation.

In observational studies, approximately 8% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 experience a bacterial or fungal co-infection, but up to 72% are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics.78 Awaiting further data, it may be prudent to withhold antibacterial drugs in patients with COVID-19 and reserve them for those who present with radiological findings and/or inflammatory markers compatible with co-infection or who are immunocompromised and/or critically ill.72

Targeting the Virus and the Host Response

The following classes of drugs are being evaluated or developed for the management of COVID-19: antivirals (eg, remdesivir, favipiravir), antibodies (eg, convalescent plasma, hyperimmune immunoglobulins), anti-inflammatory agents (dexamethasone, statins), targeted immunomodulatory therapies (eg, tocilizumab, sarilumab, anakinra, ruxolitinib), anticoagulants (eg, heparin), and antifibrotics (eg, tyrosine kinase inhibitors). It is likely that different treatment modalities might have different efficacies at different stages of illness and in different manifestations of disease. Viral inhibition would be expected to be most effective early in infection, while, in hospitalized patients, immunomodulatory agents may be useful to prevent disease progression and anticoagulants may be useful to prevent thromboembolic complications.

More than 200 trials of chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine, compounds that inhibit viral entry and endocytosis of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and may have beneficial immunomodulatory effects in vivo,79,80 have been initiated, but early data from clinical trials in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 have not demonstrated clear benefit.81–83 A clinical trial of 150 patients in China admitted to the hospital for mild to moderate COVID-19 did not find an effect on negative conversion of SARS-CoV-2 by 28 days (the main outcome measure) when compared with standard of care alone.83 Two retrospective studies found no effect of hydroxychloroquine on risk of intubation or mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19.84,85 One of these retrospective multicenter cohort studies compared in-hospital mortality between those treated with hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin (735 patients), hydroxychloroquine alone (271 patients), azithromycin alone (211 patients), and neither drug (221 patients), but reported no differences across the groups.84 Adverse effects are common, most notably QT prolongation with an increased risk of cardiac complications in an already vulnerable population.82,84 These findings do not support off-label use of (hydroxy)chloroquine either with or without the coadministration of azithromycin. Randomized clinical trials are ongoing and should provide more guidance.

Most antiviral drugs undergoing clinical testing in patients with COVID-19 are repurposed antiviral agents originally developed against influenza, HIV, Ebola, or SARS/MERS.79,86 Use of the protease inhibitor lopinavir-ritonavir, which disrupts viral replication in vitro, did not show benefit when compared with standard care in a randomized, controlled, open-label trial of 199 hospitalized adult patients with severe COVID-19.87 Among the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors, which halt SARS-CoV-2 replication, being evaluated, including ribavirin, favipiravir, and remdesivir, the latter seems to be the most promising.79,88 The first preliminary results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 1063 adults hospitalized with COVID-19 and evidence of lower respiratory tract involvement who were randomly assigned to receive intravenous remdesivir or placebo for up to 10 days demonstrated that patients randomized to receive remdesivir had a shorter time to recovery than patients in the placebo group (11 vs 15 days).88 A separate randomized, open-label trial among 397 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who did not require mechanical ventilation reported that 5 days of treatment with remdesivir was not different than 10 days in terms of clinical status on day 14.89 The effect of remdesivir on survival remains unknown.

Treatment with plasma obtained from patients who have recovered from viral infections was first reported during the 1918 flu pandemic. A first report of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 treated with convalescent plasma containing neutralizing antibody showed improvement in clinical status among all participants, defined as a combination of changes of body temperature, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen, viral load, serum antibody titer, routine blood biochemical index, ARDS, and ventilatory and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation supports before and after convalescent plasma transfusion status.90 However, a subsequent multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial of 103 patients in China with severe COVID-19 found no statistical difference in time to clinical improvement within 28 days among patients randomized to receive convalescent plasma vs standard treatment alone (51.9% vs 43.1%).91 However, the trial was stopped early because of slowing enrollment, which limited the power to detect a clinically important difference. Alternative approaches being studied include the use of convalescent plasma-derived hyperimmune globulin and monoclonal antibodies targeting SARS-CoV-2.92,93

Alternative therapeutic strategies consist of modulating the inflammatory response in patients with COVID-19. Monoclonal antibodies directed against key inflammatory mediators, such as interferon gamma, interleukin 1, interleukin 6, and complement factor 5a, all target the overwhelming inflammatory response following SARS-CoV-2 infection with the goal of preventing organ damage.79,86,94 Of these, the interleukin 6 inhibitors tocilizumab and sarilumab are best studied, with more than a dozen randomized clinical trials underway.94 Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib, are studied for their potential to prevent pulmonary vascular leakage in individuals with COVID-19.

Studies of corticosteroids for viral pneumonia and ARDS have yielded mixed results.72,73 However, the Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, which randomized 2104 patients with COVID-19 to receive 6 mg daily of dexamethasone for up to 10 days and 4321 to receive usual care, found that dexamethasone reduced 28-day all-cause mortality (21.6% vs 24.6%; age-adjusted rate ratio, 0.83 [95% CI, 0.74-0.92]; P < .001).95 The benefit was greatest in patients with symptoms for more than 7 days and patients who required mechanical ventilation. By contrast, there was no benefit (and possibility for harm) among patients with shorter symptom duration and no supplemental oxygen requirement. A retrospective cohort study of 201 patients in Wuhan, China, with confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia and ARDS reported that treatment with methylprednisolone was associated with reduced risk of death (hazard ratio, 0.38 [95% CI, 0.20-0.72]).69

Thromboembolic prophylaxis with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin is recommended for all hospitalized patients with COVID-19.15,19 Studies are ongoing to assess whether certain patients (ie, those with elevated D-dimer) benefit from therapeutic anticoagulation.

A disproportionate percentage of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths occurs in lower-income and minority populations.45,96,97 In a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of 580 hospitalized patients for whom race data were available, 33% were Black and 45% were White, while 18% of residents in the surrounding community were Black and 59% were White.45 The disproportionate prevalence of COVID-19 among Black patients was separately reported in a retrospective cohort study of 3626 patients with COVID-19 from Louisiana, in which 77% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and 71% of patients who died of COVID-19 were Black, but Black individuals comprised only 31% of the area population.97,98 This disproportionate burden may be a reflection of disparities in housing, transportation, employment, and health. Minority populations are more likely to live in densely populated communities or housing, depend on public transportation, or work in jobs for which telework was not possible (eg, bus driver, food service worker). Black individuals also have a higher prevalence of chronic health conditions than White individuals.98,99

Overall hospital mortality from COVID-19 is approximately 15% to 20%, but up to 40% among patients requiring ICU admission. However, mortality rates vary across cohorts, reflecting differences in the completeness of testing and case identification, variable thresholds for hospitalization, and differences in outcomes. Hospital mortality ranges from less than 5% among patients younger than 40 years to 35% for patients aged 70 to 79 years and greater than 60% for patients aged 80 to 89 years.46 Estimated overall death rates by age group per 1000 confirmed cases are provided in the Table. Because not all people who die during the pandemic are tested for COVID-19, actual numbers of deaths from COVID-19 are higher than reported numbers.

Although long-term outcomes from COVID-19 are currently unknown, patients with severe illness are likely to suffer substantial sequelae. Survival from sepsis is associated with increased risk for mortality for at least 2 years, new physical disability, new cognitive impairment, and increased vulnerability to recurrent infection and further health deterioration. Similar sequalae are likely to be seen in survivors of severe COVID-19.100

Prevention and Vaccine Development

COVID-19 is a potentially preventable disease. The relationship between the intensity of public health action and the control of transmission is clear from the epidemiology of infection around the world.25,101,102 However, because most countries have implemented multiple infection control measures, it is difficult to determine the relative benefit of each.103,104 This question is increasingly important because continued interventions will be required until effective vaccines or treatments become available. In general, these interventions can be divided into those consisting of personal actions (eg, physical distancing, personal hygiene, and use of protective equipment), case and contact identification (eg, test-trace-track-isolate, reactive school or workplace closure), regulatory actions (eg, governmental limits on sizes of gatherings or business capacity; stay-at-home orders; proactive school, workplace, and public transport closure or restriction; cordon sanitaire or internal border closures), and international border measures (eg, border closure or enforced quarantine). A key priority is to identify the combination of measures that minimizes societal and economic disruption while adequately controlling infection. Optimal measures may vary between countries based on resource limitations, geography (eg, island nations and international border measures), population, and political factors (eg, health literacy, trust in government, cultural and linguistic diversity).

The evidence underlying these public health interventions has not changed since the 1918 flu pandemic.105 Mathematical modeling studies and empirical evidence support that public health interventions, including home quarantine after infection, restricting mass gatherings, travel restrictions, and social distancing, are associated with reduced rates of transmission.101,102,106 Risk of resurgence follows when these interventions are lifted.

A human vaccine is currently not available for SARS-CoV-2, but approximately 120 candidates are under development. Approaches include the use of nucleic acids (DNA or RNA), inactivated or live attenuated virus, viral vectors, and recombinant proteins or virus particles.107,108 Challenges to developing an effective vaccine consist of technical barriers (eg, whether S or receptor-binding domain proteins provoke more protective antibodies, prior exposure to adenovirus serotype 5 [which impairs immunogenicity in the viral vector vaccine], need for adjuvant), feasibility of large-scale production and regulation (eg, ensuring safety and effectiveness), and legal barriers (eg, technology transfer and licensure agreements). The SARS-CoV-2 S protein appears to be a promising immunogen for protection, but whether targeting the full-length protein or only the receptor-binding domain is sufficient to prevent transmission remains unclear.108 Other considerations include the potential duration of immunity and thus the number of vaccine doses needed to confer immunity.62,108 More than a dozen candidate SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are currently being tested in phase 1-3 trials.

Other approaches to prevention are likely to emerge in the coming months, including monoclonal antibodies, hyperimmune globulin, and convalscent titer. If proved effective, these approaches could be used in high-risk individuals, including health care workers, other essential workers, and older adults (particularly those in nursing homes or long-term care facilities).

This review has several limitations. First, information regarding SARS CoV-2 is limited. Second, information provided here is based on current evidence, but may be modified as more information becomes available. Third, few randomized trials have been published to guide management of COVID-19.

As of July 1, 2020, more than 10 million people worldwide had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Many aspects of transmission, infection, and treatment remain unclear. Advances in prevention and effective management of COVID-19 will require basic and clinical investigation and public health and clinical interventions.

Accepted for Publication: June 30, 2020.

Corresponding Author: W. Joost Wiersinga, MD, PhD, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, the Netherlands (w.j.wiersinga@amsterdamumc.nl).

Published Online: July 10, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12839

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Wiersinga is supported by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research outside the submitted work. Dr Prescott reported receiving grants from the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HCP by R01 HS026725), the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs outside the submitted work, being the sepsis physician lead for the Hospital Medicine Safety Continuous Quality Initiative funded by BlueCross/BlueShield of Michigan, and serving on the steering committee for MI-COVID-19, a Michigan statewide registry to improve care for patients with COVID-19 in Michigan. Dr Rhodes reported being the co-chair of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign. Dr Cheng reported being a member of Australian government advisory committees, including those involved in COVID-19. No other disclosures were reported.

Disclaimer: This article does not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. This material is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center. The opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of the Australian government or advisory committees.

7.

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor.

Cell. 2020;181(2):271-280. doi:

10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052PubMedGoogle Scholar

9.

Zou X, Chen K, Zou J, Han P, Hao J, Han Z. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection.

Front Med. 2020;14(2):185-192. doi:

10.1007/s11684-020-0754-0PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

11.

Fosbøl EL, Butt JH, Østergaard L, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use with COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality.

JAMA. Published online June 19, 2020. doi:

10.1001/jama.2020.11301

ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

13.

van de Veerdonk FL, Netea MG, van Deuren M, et al. Kallikrein-kinin blockade in patients with COVID-19 to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Elife. Published online April 27, 2020. doi:

10.7554/eLife.57555PubMedGoogle Scholar

14.

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia.

J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844-847. doi:

10.1111/jth.14768PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

22.

Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

J Thromb Haemost. Published online May 5, 2020. doi:

10.1111/jth.14888PubMedGoogle Scholar

24.

Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, et al; Latin American Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19 Research (LANCOVID-19). Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101623. doi:

10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623PubMedGoogle Scholar

25.

Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al; COVID-19 Systematic Urgent Review Group Effort (SURGE) study authors. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973-1987. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

28.

Chia PY, Coleman KK, Tan YK, et al; Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team. Detection of air and surface contamination by SARS-CoV-2 in hospital rooms of infected patients.

Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2800. doi:

10.1038/s41467-020-16670-2PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

30.

Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records.

Lancet. 2020;395(10226):809-815. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

38.

Byambasuren O, Cardona M, Bell K, Clark J, McLaws M, Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis.

MedRxiv. Preprint posted June 4, 2020. doi:

10.1101/2020.05.10.20097543

39.

Tabata S, Imai K, Kawano S, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in 104 people with SARS-CoV-2 infection on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: a retrospective analysis.

Lancet Infect Dis. Published online June 12, 2020. doi:

10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30482-5PubMedGoogle Scholar

41.

Cheng HY, Jian SW, Liu DP, et al. Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset.

JAMA Intern Med. Published online May 1, 2020. doi:

10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2020

ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

43.

Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application.

Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577-582. doi:

10.7326/M20-0504PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

45.

Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458-464. doi:

10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

46.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al; the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area.

JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi:

10.1001/jama.2020.6775

ArticlePubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

47.

Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al; ISARIC4C investigators. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study.

BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi:

10.1136/bmj.m1985PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

48.

The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020.

China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:10.

Google Scholar

49.

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al; COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy.

JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574-1581. doi:

10.1001/jama.2020.5394

ArticlePubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

51.

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study.

Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(8):2251-2261. doi:

10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

57.

Götzinger F, Santiago-García B, Noguera-Julián A, Lanaspa M, Lancella L, Carducci FIC. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study.

Lancet Child Adolesc Health. Published online June 25, 2020. doi:

10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30177-2PubMedGoogle Scholar

59.

Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2.

JAMA. Published online June 8, 2020. doi:

10.1001/jama.2020.10369

ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

63.

Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction-based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure.

Ann Intern Med. Published online May 13, 2020. doi:

10.7326/M20-1495PubMedGoogle Scholar

64.

Williams E, Bond K, Zhang B, Putland M, Williamson DA. Saliva as a non-invasive specimen for detection of SARS-CoV-2.

J Clin Microbiol. Published online April 21, 2020. doi:

10.1128/JCM.00776-20PubMedGoogle Scholar

65.

Guo L, Ren L, Yang S, et al. Profiling early humoral response to diagnose novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

Clin Infect Dis. Published online March 21, 2020. doi:

10.1093/cid/ciaa310PubMedGoogle Scholar

66.

Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019.

Clin Infect Dis. Published online March 28, 2020. doi:

10.1093/cid/ciaa344PubMedGoogle Scholar

67.

Bond K, Nicholson S, Hoang T, Catton M, Howden B, Williamson D. Post-Market Validation of Three Serological Assays for COVID-19. Office of Health Protection, Commonwealth Government of Australia; 2020.

73.

Wilson KC, Chotirmall SH, Bai C, Rello J; International Task Force on COVID-19.

COVID-19: Interim Guidance on Management Pending Empirical Evidence. American Thoracic Society; 2020. Accessed July 7, 2020.

https://www.thoracic.org/covid/covid-19-guidance.pdf

76.

Hager DN, Krishnan JA, Hayden DL, Brower RG; ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Tidal volume reduction in patients with acute lung injury when plateau pressures are not high.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(10):1241-1245. doi:

10.1164/rccm.200501-048CPPubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

78.

Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, et al. Bacterial and fungal co-infection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing.

Clin Infect Dis. Published online May 2, 2020. doi:

10.1093/cid/ciaa530PubMedGoogle Scholar

81.

Magagnoli J, Narendran S, Pereira F, et al. Outcomes of hydroxychloroquine usage in United States veterans hospitalized with COVID-19.

MedRxiv. Preprint posted June 5, 2020. doi:

10.1016/j.medj.2020.06.001

82.

Mahévas M, Tran VT, Roumier M, et al. Clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with covid-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data.

BMJ. 2020;369:m1844. doi:

10.1136/bmj.m1844PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

83.

Tang W, Cao Z, Han M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with mainly mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019: open label, randomised controlled trial.

BMJ. 2020;369:m1849. doi:

10.1136/bmj.m1849PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

86.

Scavone C, Brusco S, Bertini M, et al. Current pharmacological treatments for COVID-19: what’s next?

Br J Pharmacol. Published online April 24, 2020. doi:

10.1111/bph.15072PubMedGoogle Scholar

91.

Li L, Zhang W, Hu Y, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life-threatening COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial.

JAMA. Published online June 3, 2020. doi:

10.1001/jama.2020.10044

ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

93.

Brouwer PJM, Caniels TG, van der Straten K, et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies from COVID-19 patients define multiple targets of vulnerability.

Science. Published online June 15, 2020. doi:

10.1126/science.abc5902.

PubMedGoogle Scholar

95.

Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson J, Mafham M, Bell J, et al. Effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report.

medRxiv. Published online June 22, 2020. doi:

10.1101/2020.06.22.20137273:24

99.

Pham TM, Carpenter JR, Morris TP, Sharma M, Petersen I. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes diagnoses in the UK: cross-sectional analysis of the health improvement network primary care database.

Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:1081-1088. doi:

10.2147/CLEP.S227621Google ScholarCrossref

106.

Xiao Y, Tang B, Wu J, Cheke RA, Tang S. Linking key intervention timings to rapid decline of the COVID-19 effective reproductive number to quantify lessons from mainland China.

Int J Infect Dis. Published online June 11, 2020. doi:

10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.030PubMedGoogle Scholar