Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Purpose of review: We provide a summary of the epidemiology, clinical findings, management and outcomes of ethambutol-induced optic neuropathy (EON). Ethambutol-induced optic neuropathy is a well-known, potentially irreversible, blinding but largely preventable disease. Clinicians should be aware of the importance of patient and physician education as well as timely and appropriate screening.

Recent findings: Two of the largest epidemiologic studies investigating EON to date showed the prevalence of EON in all patients taking ethambutol to be between 0.7 and 1.29%, a value consistent with previous reports of patients taking the doses recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Several studies evaluated the utility of optical coherence tomography (OCT) in screening for EON. These showed decreased retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness in patients with clinically significant EON, but mixed results in their ability to detect such changes in patients taking ethambutol without visual symptoms.

Summary: Ethambutol-induced optic neuropathy is a well-known and devastating complication of ethambutol therapy. It may occur in approximately 1% of patients taking ethambutol at the WHO recommended doses, though the risk increases substantially with increased dose. All patients on ethambutol should receive regular screening by an ophthalmologist including formal visual field testing. Visual evoked potentials and OCT may be helpful for EON screening, but more research is needed to clarify their clinical usefulness. Patients who develop signs or symptoms of EON should be referred to the ethambutol-prescribing physician immediately for discontinuation or a reduction in ethambutol dosing.

Introduction

Ethambutol is a bacteriostatic antibiotic used in the treatment of Mycobacterium species. Although it is effective in treating Mycobacterium spp. in combination with other medications, one of the most common and devastating side-effects is ethambutol-induced optic neuropathy (EON). Ethambutol acts as a metal chelator. Whereas this prevents cell wall synthesis in mycobacteria by inhibiting arabinosyl transferase, it can also have a number of adverse effects on human cells as well. Although the exact mechanism of EON remains unknown, it has been hypothesized that it may result from disrupted oxidative phosphorylation secondary to decreased available copper in human mitochondria[1] or from inhibited lysosomal activation due to the chelation of zinc.[2,3]

Epidemiology

Recent estimates suggest that the prevalence of EON in patients treated for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is around 1–2%.[4–6,7**] Combined with the WHO estimates of the prevalence of M. tuberculosis, EON could affect approximately 100 000 people worldwide each year.[8] In one of the largest epidemiologic studies regarding EON to date, Chen et al.[7] in 2015 reported on the incidence of EON in 4 803 patients diagnosed with tuberculosis over a 10-year period in Southern Taiwan. They found the incidence of EON to be 1.29%, with an average ethambutol dose in these patients of 16 mg/kg per day. The study noted that ophthalmologic examinations were only available for approximately one-fourth of patients, so the true incidence may be higher. Another recent study from 2016[9] reporting on 415 nonimmunocompromised patients taking ethambutol for tuberculosis or Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease found an incidence of 0.7%. In this study, the average daily ethambutol dose was 14.5 mg/kg per day, and in patients who were taking less than 15 mg/kg per day of ethambutol, the incidence was low at 0.3% but not zero. Although these studies showed a relatively small risk of EON, the risk varies greatly with ethambutol dose.

The WHO treatment guidelines for M. tuberculosis therapy initiation include an ethambutol starting dose of 15–20 mg/kg per day.[10] Although ethambutol is often associated with tuberculosis, nontubercular mycobacterial infections are also treated with ethambutol and have different dosing. The two most commonly encountered nontubercular mycobacterial infections are M. avium complex and Mycobacterium kansasii.[11] Initial dosing recommendations from the American Thoracic Society for the treatment of these infections range from 15 mg/kg per day for M. kansasii to 25 mg/kg per day for macrolide-resistant M. avium complex.[11] The variability in initial dosing is important as EON is a dose-dependent toxicity. At doses of ethambutol as less as 15 mg/kg per day the risk of EON is less than 1%.[9] With higher doses of 20, 25, and more than 35 mg/kg per day the risk estimates increase to 3, 5–6, and 18–33%, respectively.[9,12–14] Table 1 shows recommended starting doses for the most common mycobacterial infections and Table 2 shows the estimated prevalence of EON at several different doses. Ophthalmologists following patients on ethambutol should be aware of these dose-dependent differences as patients with nontubercular mycobacterial infections may be at greater risk for EON due to higher dosing of ethambutol.

Other risk factors other than dose for the development of EON have also been identified. A 2012 case-control study with a sample of 231 patients found that age greater than 65 years, hypertension, and the presence of renal disease were associated with a greater risk of developing EON.[6] Other studies have also identified renal dysfunction as a major risk factor for development of EON.[4,15] As ethambutol is excreted by the kidneys, prescribers of ethambutol and those monitoring for vision changes should be especially vigilant with patients who have renal disease. In addition, concomitant isoniazid therapy, that has been independently associated with a similar optic neuropathy in several case reports,[16–18] in combination with ethambutol for treatment of Mycobacterium spp. may put patients at greater risk for development of optic neuropathy.[19–21] Many authors recommend discontinuing the isoniazid if patients do not respond or continue to progress after discontinuation of the ethambutol in suspected cases of EON.

Clinical Presentation

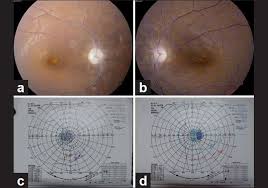

Patients presenting with EON typically complain of subacute, bilateral, painless, and typically symmetric loss of central vision. Patients may describe cloudy or blurry vision, difficulty reading, difficulty distinguishing colors, or frequent changes in eyeglass or contact lens prescription.[4] Unlike other more commonly known visual toxicity agents (e.g. hydroxychloroquine), where long durations of therapy are required for toxicity, EON may begin rapidly between 1 month and 36 months after beginning therapy. In general, however, most patients experience visual symptoms within the first 9 months of treatment.[4,5,7] In more than 60% of patients, physical examination reveals bilateral, painless, and typically symmetric loss of visual acuity as well as abnormal color vision. Color vision loss is typically in distinguishing green and red, though blue–yellow color changes may also occur.[4,5,22–24] Initially the optic nerve is normal but eventually optic disc pallor will develop. If optic atrophy is present at onset, it is generally considered to be a poor prognostic sign.[4] Visual field testing most often reveals central or cecocentral scotoma,[4,7,25] though bitemporal break out of the visual field defect with optic chiasm involvement has also been reported (see Figure 1).[26–29] Visually evoked potentials (VEP) may reveal abnormalities in the amplitude or latency of the p100 wave.[4,30,31,32]

Figure 1.

Humphrey visual field with foveal threshold of 26 decibels showing bitemporal hemianopsia representing toxicity of the optic chiasm.

Screening for Clinical Ethambutol-induced Optic Neuropathy

Primary prevention of EON is the best treatment. This includes regular screening for visual changes. Patients started on ethambutol should be appropriately educated about the possibility of visual loss and the need for screening and follow-up with an ophthalmologist, as well as the need to seek care immediately if they notice any visual disturbances. Baseline examination immediately prior to or at the time of ethambutol treatment initiation should include visual acuity, formal visual field testing, color vision testing, and dilated fundus examination. Follow-up screening should be done on a monthly basis in high-risk patients (preferably by an eye care specialist) and testing should include at least visual acuity check and Amsler grid testing. Patients could be given an Amsler grid or pocket Snellen chart for use at home to test their own vision in between visits to the eye care provider. Whenever vision changes are detected by the patient or eye care provider, however, the primary prescribing physician should be contacted regarding the decision to continue or discontinue ethambutol. A temporary suspension of treatment can be considered based upon the risk–benefit ratio and consultation with the prescribing physician until the diagnostic evaluation of the visual loss can be completed.

Screening for Subclinical Ethambutol-induced Optic Neuropathy

Of significant interest to prescribing physicians and ophthalmologists are methods to screen for preclinical signs of EON so as to stop ethambutol before vision loss occurs. Visually evoked potentials and optical coherence tomography (OCT) have been used to assess subclinical visual impairment in patients with optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis,[33–35] and are under investigation for their potential role in detecting subclinical EON. In addition, multifocal electroretinogram (MfERG) has been used to successfully detect retinopathies due to toxicity from medications such as chloroquine,[36] and may be able to detect retinal damage secondary to ethambutol toxicity.

Visual Evoked Potentials

Visual evoked potentials or visual evoked responses are small electrical signals generated in the occipital cortex following a brief visual stimulus. The p100 wave is a positive deflection that occurs on an average 100 ms after the visual stimulus. An increased latency of the p100 is a well-established tool in the diagnosis of optic nerve disease such as optic neuritis,[37] though the exact amount that constitutes an abnormality varies by machine. The utility of VEP for detecting subclinical abnormalities in patients taking ethambutol is less well established.

Several studies have found increased p100 wave latency in patients diagnosed with EON.[4,7,22,32] In 2008, a study of 857 patients showed that increased latency (mean 127.7 ms) was found in 65.4% of the eyes in patients diagnosed with EON. In a 2015 study[7] five of nine patients with EON on whom VEP was conducted had increased latency. In this study, the amount of latency was not specified and VEP was not conducted on 53 of the 62 patients with EON. Other studies have also evaluated the effect of ethambutol therapy on p100 latency regardless of EON status.[30,38–41] A study of 31 patients in 2016[30] reported data showing that the mean p100 latency increased from 101 to 106.4 and 115.1 ms at 2 and 4 months, respectively. Another study reported changes in VEP p100 latency in terms of the percentage of patients who had increased latency beyond a given cut-off value derived from the VEP p100 of study controls.[41] They found that 34.8% of patients taking ethambutol had increased latency beyond 107 ms, 2 SD beyond the control mean of 97 ms. Other studies have produced similar results.[38,39]

Taken together these results show promise for the utility of VEP for EON screening, but more research is needed to better understand its usefulness for this purpose clinically. At this time, the use of VEP for EON screening must be done with a word of caution. Although a finding of increased p100 latency may indicate decreased function of the optic nerve, it is not yet clear how many of these patients will go on to develop clinical EON. In addition, VEP testing is not readily available to all clinicians and patients. Any decision to discontinue ethambutol or change the dosing should be made by the prescribing physician following a discussion in which risk of possible EON is weighed against the risk of potentially suboptimal antituberculosis treatment.

Optical Coherence Tomography

OCT and measurement of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) has also proven an effective tool in the evaluation of optic neuritis and other optic neuropathies,[42] although its sensitivity in detecting subclinical disease has not been as high as VEP.[33,35] Like VEP, OCT has only been evaluated as a tool for detecting EON in a handful of small studies to date.[30,39,43,44,45–47,48*] Several studies used OCT to detect changes in the RNFL of patients with clinically significant vision loss from EON.[44,45–47] These studies demonstrated a decrease in RNFL thickness of 20–79%.[45,47] However, the value of OCT depends on its ability to reliably detect subclinical EON so that ethambutol therapy may be adjusted before vision loss occurs. In studies aimed at detecting subclinical EON, the findings have not been validated.[30,39,43,48,49] Two studies representing 68 patients taking ethambutol actually found an increase in RNFL thickness overall or in select quadrants.[30,43] Another study detected temporal RNFL thinning in 3/104 (2.88%) of 104 eyes in patients taking ethambutol,[39] but no patient developed subsequent EON. Yet another reported aggregate RNFL thinning of approximately 5 μm[48] over 2 months, though data on individual patients was not reported. In addition to damage to the RNFL, experiments in animal models have demonstrated toxicity of the retinal ganglion cell layer.[50,51] One study in 37 patients treated with ethambutol examined changes in the ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness on OCT.[43] One patient developed EON and OCT revealed GCIPL layer thinning whereas patients without EON had no significant changes GCIPL thickness. Taken together, these findings suggest that although OCT is likely to be able to detect significant RNFL and possibly GCIPL thickness changes in patients with clinical EON, it may or may not be useful in screening patients for subclinical disease while on ethambutol therapy. More research is needed to adjudicate this question and establish OCT screening guidelines for EON.

Multifocal Electroretinography

While damage to the optic nerve is likely important in the mechanism of visual loss in many patients taking ethambutol, evidence also suggests that ethambutol may produce visual symptoms through toxicity to retinal cell layers as well.[36,43,50,51] Multifocal electroretinogram is a test especially useful in the detection of retinopathies[36] and produces a waveform with two negative deflections (N1 and N2) and one positive deflection [P1]. Abnormalities in MfERG provide early and reliable detection of retinopathies due to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine,[36] but relatively few studies have examined its utility in detecting EON. Four case series representing nine patients[52–55] have shown decreased amplitude of MfERG waves in central and nasal macular regions in patients with vision loss while taking ethambutol. In two larger studies of 17[56] and 44[57] patients taking ethambutol the researchers found decreased P1 amplitude and delayed P1 latency. None of the patients in these studies developed visual symptoms, suggesting the ability of MfERG to detect subclinical disease. More research is needed to understand the role MfERG should play in the detection of subclinical retinal toxicity in patients taking ethambutol.

Treatment

There is currently no effective treatment for EON. However, if detected early and with prompt discontinuation of ethambutol, between 30 and 64% of patients show some improvement in their visual disturbances over a period of several months.[4,5,31,58,59] In patients who show improvement, however, few will have full recovery, with an average improvement of two lines on the Snellen chart.[4,7,31] One small case series of 10 patients with EON found that in patients over 60 years old the recovery rate was only 20%, whereas it was 80% for patients less than 60 years old, suggesting that increased age may prognosticate poorer recovery.[58] Ophthalmologists who suspect EON should contact the ethambutol-prescribing provider immediately to discuss discontinuation or reduction of prescription dosing.

Understanding the pathogenesis of EON is critical to finding an effective treatment. Ocular tissue has high levels of zinc,[60] and several studies have shown that ethambutol causes chelation of zinc[3,61] as well as copper.[62] In addition, other studies have suggested other nutrients that may predict EON development. One study of 50 patients found that decreased levels of vitamin E and vitamin B were associated with EON development,[63] and a small case series reported patients who had visual recovery following cobalamin administration.[64] It is thought that EON may be in part due to a deficiency in these nutrients, particularly zinc and copper, as zinc deficiency has been found to be related to destruction of myelin and glial cell proliferation in rat optic nerves.[65] In addition, patients with low plasma zinc levels have been found to have a higher likelihood of developing EON.[66] Supplementation with zinc and copper for patients taking ethambutol has thus been proposed as a method of reducing the likelihood of EON. Importantly, such supplementation in vitro has not decreased the efficacy of ethambutol in fighting mycobacterium,[1] and did not change the rate of pulmonary TB clearance in a randomized control trial of patients taking micronutrients with ethambutol.[67] However, more research is needed to know if such supplementation is effective in reducing EON risk. Although we do not recommend routinely testing serum zinc or copper levels in patients taking ethambutol, it may provide some benefit for relatively little risk, and supplementation in patients may be undertaken at the provider’s discretion.

Ethambutol-induced Optic Neuropathy in Children

Interestingly, the prevalence of EON in children treated with ethambutol is much less than in adults. One review of the literature found the prevalence of vision loss from EON to be 0.05%, or 2 in 3 811 in children taking doses between 15 and 30 mg/kg per day,[68] and the two reported cases were not clear-cut EON.[69,70] In addition to an absence of clinical findings of EON in children, subclinical findings have also been seldom reported. In one study following 47 children on ethambutol therapy,[40] there were no differences in the latency of the p100 wave, a finding suggestive of subclinical toxicity in adults. For many years, ethambutol was used very cautiously in children of any age and its use was not recommended in children under the age of 5 because of their inability to describe changes in their vision.[68] However, these recommendations have recently changed. In 2010 the WHO raised the recommended dose of ethambutol for children to 20 mg/kg per day from the previous 14 mg/kg per day.[71] For some reason not completely understood, the serum concentration of ethambutol in children is lower than in adults for a given dose. As long as the WHO prescription guidelines are followed, the likelihood of EON in children is extremely small. Despite the low prevalence of EON in children, however, we still recommend that children taking ethambutol should be monitored.

Conclusion

Ethambutol-induced optic neuropathy is one of the most common and recognized drug-induced optic neuropathies. As ethambutol is a key component of many anti-mycobacterial treatment regimens, the number of people worldwide who may be impacted by EON each year is very high. Patients may present with a variety of symptoms including bilateral, painless, and progressive changes in visual acuity or color vision, and visual field testing often reveals a central or cecocentral scotoma. Patients receiving less than 15 mg/kg per day of ethambutol are much less likely to suffer from EON, but all patients taking ethambutol of any dose should receive regular screening from an eye care provider. Although VEP and OCT have shown some promise for becoming useful tools in detecting subclinical disease, more research is needed to understand their role in prevention. Individual providers may use these screening tools, but should recognize their limitations and should use them along with visual acuity and visual testing. If dosing recommendations are followed, the chance of developing EON in children is even less than in adults. Nevertheless, we still recommend screening in all children taking ethambutol. For individuals showing signs of EON, the ethambutol-prescribing physician should be contacted immediately. If stopped when symptoms of EON first appear, at least a third of patients will show some visual recovery. Ophthalmologists and others caring for patients treated with ethambutol should be aware of its potential toxic effects to the visual system and understand the need for regular screening to help prevent this debilitating disease.